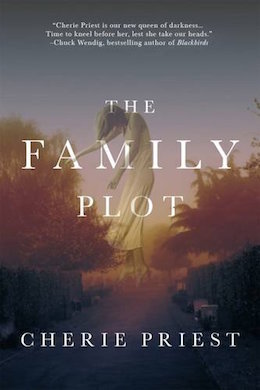

Music City Salvage is a family operation, owned and operated by Chuck Dutton: master stripper of doomed historic properties, and expert seller of all things old and crusty. But business is lean and times are tight, so he’s thrilled when the aged and esteemed Augusta Withrow appears in his office, bearing an offer he really ought to refuse. She has a massive family estate to unload—lock, stock, and barrel. For a check and a handshake, it’s all his.

It’s a big check. It’s a firm handshake. And it’s enough of a gold mine that he assigns his daughter Dahlia to personally oversee the project.

Dahlia preps a couple of trucks, takes a small crew, and they caravan down to Chattanooga, Tennessee, where the ancient Withrow house is waiting—and so is a barn, a carriage house, and a small, overgrown cemetery that Augusta Withrow left out of the paperwork. Augusta Withrow left out a lot of things. The property is in unusually great shape for a condemned building. It’s empty, but it isn’t abandoned. Something in the Withrow mansion is angry and lost. This is its last chance to raise hell before the house is gone forever, and there’s still plenty of room in the strange little family plot…

Cherie Priest’s The Family Plot is a haunted house story for the ages—atmospheric, scary, and strange, with a modern gothic sensibility that’s every bit as fresh as it is frightening. Available September 20th from Tor Books. Read chapter 2 below, in which Dalia Dutton and her employee Brad drive up to the old Withrow estate to prepare it for salvage.

Chapter 2

Brad fiddled with his phone, alternately pleading with—and bitching at—Siri. “Chattanooga,” he enunciated, trying so hard to rid the word of his Georgia accent that he formed a newer, more bizarre accent in its place. Siri didn’t recognize that one, either.

“Don’t worry about it,” Dahlia told him from the driver’s seat. “It’s a straight shot on the interstate from here. We won’t need directions until we hit Saint Elmo, and I doubt the phone will be any good when it comes to finding this house. From the way Dad talked, its road isn’t really paved.”

“Then how are we supposed to find it? Did he draw you a map, or something?”

“Yes,” she lied. Chuck had given her directions, but she wasn’t overly confident she could read them. His handwriting had never been any better than chicken scratch, so her real plan was to (a) take her best crack at translating them, and then probably (b) ask around once they hit the historic district. Somebody, somewhere, was bound to know the spot.

Brad stuff ed the phone away in his sweater pocket, put his feet up on the dash, then pulled them down again. He opened the glove box, and shut it again. He tapped his knuckle on the door’s built-in cupholder.

“If you’re going to fidget like that all the way to Lookout, you can ride in the back with our gear.”

“Sorry. I’m sorry. I’m just nervous. This is… this is weird, isn’t it?” He turned to her, eyeing her through spectacles that might’ve been for show. Bless his heart, he wasn’t dressed for demo. He was wearing khakis and a pullover, and a pair of Converse sneakers, as a nod toward some latent hipsterism he should’ve outgrown a decade ago. He was thirty, but he sure as hell seemed younger.

“What do you mean, weird?”

“Sleeping in the house, while we’re breaking it down. That’s weird, right?”

“I’ve done it before. It’s not that bad, and it saves a lot of money. So it’s definitely not weird.”

He played with his watch. It was a nice one. Expensive, with a retro design. He had no business wearing it to a salvage site, but whatever—he’d learn the hard way. “We’re going to be there, like… a week. Does it always take a week?”

“No, but this is a big job and we’re short-staffed. Try to think of it as a week of on-the-job training.” She smiled grimly, and stared straight ahead at the road.

“I can’t wait.”

“Try not to sound so excited. Dad warned you, this gig isn’t indoor work with no heavy lifting, so a little manual labor shouldn’t come as a big surprise.”

“I’m not surprised. I’m…”

When he didn’t finish the thought, she flashed him a glance. “Disappointed? Your résumé says academia. So do your hands.”

“Is that an insult?”

“No, and don’t take it like one. I always wanted a few letters behind my name, myself. But I only survived two years of college before giving up and coming home. I figured out I could learn more from the ware house than a textbook, and it didn’t cost me thousands of dollars a semester. I got paid for my trouble, instead of going into debt.”

She didn’t get paid enough to go back and finish. She left that part out.

Brad put his feet back up on the dash. His shoes squeaked on the underside of the windshield as he pressed his toes against it. “Yeah,” he said sadly. “It’s a lot of money. And unlike us credentialed losers, you won’t be paying your student loans until social security kicks in.”

“True. I ought to have them all killed off before I’m forty. But no one said anything about you being a loser.” Because she wondered, she bluntly asked, “Do you feel like a loser, working at Music City?”

“No,” he insisted quickly. “I’m grateful for the gig. Your dad gave me a chance, and I know I’m not the sort of guy he usually brings on board. But… honestly? This job is only tangential to my field—so I feel like I’ve gone a little… offtrack. I thought I was destined for tenure and a foxy grad assistant, not… not…”

“Power tools and rust. I get it. You don’t have to explain yourself.”

“I’m not the puss you guys think I am.”

“No one said you were a puss, either.”

“Not to my face, so thanks for that.” He wiggled his toes some more, then realized what he was doing and stopped before Dahlia had to make him. “I know I’m not part of the tribe.”

“You’re not part of the family. Right now, that’s a point in your favor.” The last bit came out with a grumble.

“Yeah, what’s up with that, anyway? Chuck said you and Bobby grew up close, but you obviously hate each other now.”

She took a deep breath that turned into a sigh. “It’s not… we don’t… we don’t hate each other. Exactly.”

“Well, you’re awful pissed at him.” For a guy with a fistful of degrees, he sure sounded corn-fed when he put two syllables in “pissed.” Maybe he kept the accent out of pure defiance, a stalwart middle finger to the academic masses who looked down on it. Or maybe he couldn’t shake it, not for trying.

“You’re right about that. You want the short version?”

“Short, long. Surprise me.”

“Okay, then you can have the middle version: I got divorced this year. My ex-husband is Bobby’s best friend, and Bobby picked sides. It’s the same old bullshit as always. He’s always had this… knack… for choosing the wrong company, and being a little too dumb to keep himself out of trouble.”

“I know his wife’s in jail. Office gossip, you know.”

“She went away for identity theft and fraud charges,” Dahlia supplied. “Yeah, Gracie’s a piece of work. I never liked her, and Bobby finally divorced her about five years ago. He got the car, and she got Gabe, plus a fat stack of IOUs instead of child support. He was unemployed back then.”

“Bobby wasn’t working here?”

“Nah. He’s worked for us before, off and on—summers in high school, a job or two at a time when we needed a warm body and he needed beer money. But he’s only been on the payroll for a few months. Dad took pity on him when Gracie went up the creek, so I guess he came on board right before you did.”

“Does he do good work?”

“He knows how to do good work.”

“A fine distinction.”

“Heh.” She started to smile, but the other Music City Salvage truck darted into the passing lane. She saw it in the side mirror, and her brewing mirth evaporated. Bobby was talking in an animated fashion as he pressed the gas, pulling up alongside her. Gabe looked bored. She said, “All you need to know about Bobby is this: good work, completed on time, zero bitching. Pick two.”

“Gotcha.”

Her cell phone rang, vibrating beside the gearshift with a tinny rattle. It was Gabe. He waved at her from the other truck.

She waved back, and answered the call. “You guys need a pit stop?”

“Dad wants coffee. I could use a Coke.”

“There’s a McDonald’s at the next exit; I’ll see you there.” She hung up and asked Brad, “You want anything?”

“I wouldn’t say no to some coffee.”

“Me either. I’m not usually up this early.”

When the brief detour was accomplished, she took the lead again. Somewhere around Monteagle, Bobby drew up to pass her, but she gunned the engine and wouldn’t let him. She could practically hear him swearing back there, undoubtedly deploying one of his favorite expressions, stolen from a T-shirt, something about how if you’re not the lead dog, the view never changes. He was probably trying to turn it into a life lesson for his son, who—thank God—was smart enough to recognize bluster and bullshit when he heard it.

She hoped.

The trucks took the Lookout Mountain exit around nine o’clock, and rolled under a railway pass into Saint Elmo a few minutes later.

It was a cute little place, in Dahlia’s opinion—a Victorian enclave built around a tiny town center, nestled against the foot of the mountain. The Incline passenger railway launched from the middle, across from restaurants and a coffee shop. At first she didn’t see anyplace to pull over and regroup, but then she spied a big, half-empty pay lot beside the Incline tracks. She pulled over there, and waited for Bobby to draw up beside her.

When he did, they rolled down their windows in unison. He asked, “Do you know how to get to this house?”

“Only sort of,” she confessed. “You know Dad’s handwriting. You want me to try and find it, then come get you? The road’s not paved, and we might have trouble turning both trucks around if we get lost.”

“Sounds like a plan.” Bobby was always happy to sit around with his thumb up his ass while someone else did the work. “Do you think they’ll try and make us pay for parking?”

“Not if you’re still sitting in the cab. Pretend you pulled over to take a phone call or something, if anybody asks. One way or another, I’ll be back in ten.”

She rolled up the window and reached over Brad to fish around in the glove box. She pulled out a red spiral-bound notebook that was beat all to hell, and opened it up to a page her dad had dog-eared. “South Broad Street,” she translated. “That’s the road right there. There ought to be a stoplight around the bend. The road splits, and the highway goes up the mountain. I think.”

“You don’t really know, do you?”

“Worst-case scenario, I’m wrong, we get lost, and we’re eaten by cannibal rednecks.”

“Dear God.”

“Or we could just stop and ask for directions.”

“Or that.” He gazed out the window at a row of buses. “I don’t know. This looks like a little tourist town, or something. Prob ably not a lot of cannibalism. Only a few banjos.”

“That’s the spirit.”

Dahlia put the truck into gear and pulled back out of the lot, leaving the directions sitting in her lap. She found the stoplight, marked with a historic designation sign, and a couple of stone monuments she didn’t have time to read. Then up the mountain she went, on a crooked two-lane road that was steep enough to slide down, and barely wide enough to hold the twenty-six-foot truck’s wheels between the lines. One tire skidded on fallen leaves and ground them into a slippery goo on the median. She swore, pulled closer to the middle, and kept on driving through a canopy half changed for autumn, and still falling by the day.

In another month, Lookout would be bald and wearing a ring of frost at its crown. But this was the start of October, and the air was only cool and a little windy. It didn’t even shove the truck from side to side, and there was no need for either AC or heat.

She put the window down again, partly to enjoy the weather, and partly to get a better look at any signs she might otherwise miss. “Keep your eyes peeled for ‘Wildwood Trail.’ ”

“Is that it?”

A green city street sign leaned to the south, bent by accident or vandalism. She cocked her head to read it. “Yup. Good call.” She took the turn with a smooth pull of the wheel, onto a strip that was blessed with asphalt, but no medians or guiding paint stripes. “Now we’re looking for the turnoff to the estate. It should be up here on the right, in another half mile.”

“This says it’s covered by… a bath? Is that what it says? That can’t be right…”

“Gate,” she corrected him without looking. She’d already decoded that particular bit of script. “Supposedly there’s a gate, but it isn’t locked. Like, it’s barred off to keep cars out, but… you know what? I have no idea what it actually looks like. We’ll find out when we get there.”

On both sides of the allegedly two-way thoroughfare, sheer rock faces came and went, and boulders the size of toolsheds broke up the gullies and pockets of trees. Finally, beneath an arch of ancient dogwood branches, they spotted a long, rusted triangle with one end lying on the ground. “That must be it.”

“That’s not a gate. That’s a knee-high obstacle, and it’s about to fall over.”

“I can see that, but I’m still not driving over it,” she told him. “Get out and move it for me, would you?”

He opened the door and hopped down onto the leaf-littered street, tiptoeing up to the edge of the turnoff. He looked back at the truck, but Dahlia just waved her arms at him and said, “Go on…,” loud enough that he prob ably heard her.

He bent over and pulled, lifting the simple barrier and dragging it over to the ditch. He dumped it alongside one of the dogwoods, and flashed a thumbs-up before scrambling back into the cab. “I hope you’re happy. Now I need a tetanus shot.”

“You haven’t had one recently?”

“Not… super recently.”

“Jesus, Brad. When we get back to Nashville, I’m running you past a doc-in-a-box to get that fixed. Maybe even sooner, depending on what we find here. You need your shots, if you’re going to work these sites. Lockjaw ain’t pretty.”

He held his rust-covered hands aloft, like he didn’t want to touch anything—or he was looking for someplace to wipe them. Giving up, he smeared them across the top of his thighs.

“I was going to say to clean your hands on the seat, ’cause Dad’ll never know the difference. But I like the decision to run with your pants. It shows promise.”

“They’re old and ratty. That’s why I’m wearing them. I brought jeans, too, I’ll have you to know.”

She nodded, and patted his shoulder. “Good for you, Sunshine. Now put your seat belt back on. Let’s go find this place.”

Starting at a crawl, she drew the truck forward. Its top scraped the undersides of the trees with a noise like fingernails on a pie plate. Dahlia cringed, but pushed forward—and on the other side, the way was clearer than expected.

The road was so overgrown you could hardly call it a road, but it was wider than the erstwhile highway behind them, and the truck’s axles were high enough to miss the worst of the brambles, shrubbery, and monkey grass that reached up to tickle the undercarriage. They drove on, to the swishing sound of vines and the damp crunch of rotting branches beneath the tires… angling the truck up and around on the mountain’s eastern face, where the morning light shot sharply between the trees.

“How much farther, do you think?”

“See those pillars?” She pointed at a tall pair of crumbling stone columns, with one corroded iron gate hanging ajar by a single hinge. It’d once been part of a pair that closed together, but the other had long since fallen and been dragged away or scrapped. There was plenty of room to drive between the old sentinels, but she did it slow, in a cautious creep. Beyond those columns there was a stretch, and a bend, and then… at long last, the Withrow estate.

The photos hadn’t done it justice, but Brad almost did, when he whispered, “Holy shit…”

The main house was two and a half stories tall. Once it might’ve been blue—but over time it’d faded like anything will if left too long in the rain. Now its columns, wood slat siding, and jagged remnants of gingerbread were all the color of laundry water. A rickety widow’s walk stretched across the roof, accompanied by a skyline of snaggle-toothed chimneys—along with a fat, round turret wearing a spiral of weathered cedar shingles. A wraparound porch sagged out front and around to the north side, weighed down by a century of Virginia creeper, English ivy, and a dull green tsunami of kudzu.

“‘Holy shit’ is right,” Dahlia agreed.

“You really think we can salvage this place in five days?”

“The house? Sure, no big deal. But the house, plus the barn…” she said, pointing at the property’s westernmost corner. “And the carriage house beside it… damn. Now I wish I hadn’t made any promises. If we had a full crew, it’d be easy enough. But with just the four of us… Then again, Dad’ll be here on Friday.”

She pulled the truck around so it faced the house, perched with its back to the slope.

“This place was beautiful once,” Brad marveled.

“It still is.” Dahlia left the engine running, but opened her door and hopped down onto the yard. There wasn’t any driveway, and no one would care if she left a few tire tracks. The bulldozers would do worse, come the fifteenth. She frowned at the thought. “Hey, Brad?”

“Yes ma’am?”

“You think you can find your way back to Bobby and Gabe? And bring them here?”

“I think so. It’s only a couple of turns.”

“Great. Then the truck’s all yours, if you’ll go and fetch the boys. I’ll open the place up, take a look around, and start prioritizing our demo plans.”

“Okay. I’ll be right back.” He scooted over from the passenger’s seat and slid behind the wheel, then pulled the door shut.

“Take your time.” She gave him a parting wave, but didn’t look back to watch him go.

Truth was, she wanted a moment alone with the house, with nobody watching or listening. She tried to steal that kind of moment on every job, and she didn’t always get it. Sometimes, she had to say her piece in a busy room, buzzing with saws and the thunk of pry bars biting into paneling. Sometimes she had to whisper it like a little prayer from the backyard, while forklifts pulled windows from their casings.

The truck rolled away, leaving her alone in front of the massive house.

She took the handrail and, one by one, she scaled the sinking stairs, where the creaking crunch of bug-eaten wood caused the small things under the steps to scatter. At the top, she found a porch cluttered with seasonally abandoned bird nests, brittle veins of creeper vines, and small drifts of fall’s first offerings from the nearby oaks and maples.

The boards bowed beneath her feet as she stood before the great carved door, with its leaded glass transom and sidelights, and she tried not to think of the business—of the butchery to come. She tried not to calculate how hard or how easy it would be to remove the whole door in one piece with its transom and sidelights, or consider what Music City might sell it for. Ten grand, that’s the price tag her dad would pick. Ten grand, unless they broke something.

She pushed the numbers out of her head, and pushed Augusta Withrow’s old key into the lock. It stuck, but turned, and the door opened with hardly a squeak. It swayed inside like the arm of a butler.

“Hello,” she announced herself as she crossed the threshold, into the foyer. The ceilings were high, and the room dividers on either side had curvy white columns atop them. She breathed in the stale old air like it was sweet and fresh. She came farther inside. “My name is Dahlia Dutton, and I’m sorry about what’s coming. I want you to know, it isn’t up to me. I’d save you if I could, but I can’t—so I’ll save what pieces I can. In that way, you’ll live on someplace else. That’s all I can offer. But I promise, I will take you apart with love… and I’ll never forget you.”

Her words hung in the speckled, dusty air. The broad, open space was gold with morning sun, filtered through long curtains in the parlor and sitting room, each drape as frail and light as cheesecloth. Dahlia went to those curtains, window by window, and carefully pulled them open. Their bottom hems dragged patterns in the dust.

Overhead, just inside the front door, a big light fixture stopped short of being a chandelier. Not enough crystals were strung across it, and it didn’t have enough glittering bulk. It’d be categorized as a “large pendant” when it hit the ware house floor.

“Old, but definitely not original,” she observed, her voice stuck in that reverent whisper she always used in old places when no one was around to hear her.

She wouldn’t feel so bad about taking the pendant, but much of what she saw was original to the house, left over from the estate’s very beginnings.

The front door behind her and its leaded windows, those were certainly first run—and now that she was inside looking out, she noticed a rose-like pattern with trailing vines across the arched transom. “Eleven grand,” she updated her assessment. It was one of Chuck’s rules: If it’s Victorian, and it has roses… add a thousand to the asking price. People will pay it.

The staircase, oh, that was entirely original. Like everything else, it was coated in a thick gray fluff of cobwebs, dust, and the sawdust of insect damage, but the chestnut bones were amazing, and when Dahlia put her hand on the rail, it held without the slightest wiggle.

The sawdust idly worried her. Termites? Carpenter bees? Ants? Could be anything, but she hoped it was nothing. It didn’t matter, anyway, as long as the bugs had left the wainscoting and baseboards alone. Those bits looked solid enough, and they didn’t budge when she pushed her fingers or toes against them.

She looked up past the pendant light, and around the ceiling. The whole thing was plaster, cracked with Rorschach lines radiating from both the southern corner and the light’s elaborate scrolled medallion. She knew without checking that the trim would be plaster, too. Unfortunately—it was beautifully shaped, but it’d crumble at the first touch of a pry bar. Oh well.

“Can’t save it all,” she murmured. “Lord knows, I wish it were different.”

Dahlia stopped at the foot of the stairs and mentally mapped the place. She stood at the edge of a formal common area. Beyond it was the foyer and front door. To her right was a large parlor with a worn, round rug as its only furnishing; but she spied a set of bay windows that might be sturdy enough to come out in one piece. There was a fireplace in there, certainly. Prob ably one with a marble surround, since it was a room where company would wait. She couldn’t see it from where she was taking her survey, but it must be on the far wall.

To her left, she noted a formal dining room. It was off set by an opening that held a pair of pocket doors, or so she hoped. It had one pocket door, at least—half extended, partially block.ing the thoroughfare. The door had a wood frame, with glass panels and brass inlay details. If the other door was present and intact, and if she could extract them both, along with their rails and wheels, then Dad could probably ask…

…but no, she was doing it again, assigning price tags be.fore it was time. It felt sacrilegious somehow, almost like auctioning off human organs before the donor has passed. Chuck had once accused her of being morbid when she told him that. He said you couldn’t compare a house to a living, breathing person—it wasn’t the same thing. In her sentiment, that was the sacrilege, right there.

Standing there in the Withrow house, she felt a deep sorrow anyway. It was an acute thing, a sense of grieving that the great old structure surely warranted. And maybe it was only a silly, blasphemous notion, but the mansion was such a lost thing. A sad thing, a tragic thing that deserved a better fate than the one it had coming.

An angry thing.

A chill ran from the back of her neck to her knees.

Angry?

Dahlia spent a lot of time angry these days, but the houses themselves were never anything but mournful. Had she called the word to mind, or had she heard it? Now she heard nothing, only that weird, white silence of a place that’s been so long closed up and unloved.

Unloved.

The word echoed between her ears, another odd intrusion. She shook her head, but it rang very faintly, a tinnitus-pitched hum that might mean a migraine was coming, or might only mean that her allergies were flaring up. She chose to believe it was the dust, because she didn’t have time for a headache. She carried medicine in her satchel for those unexpected just-in-case times of outrageous pain or congestion; but she’d left her bag in the truck.

It’d come back to her soon enough, along with the cooler in the back, stuffed with water, Gatorade, and Monster Energy drinks. Great for refreshment and popping pills alike.

In the meantime, there was plenty of house to see, and nothing she could do about the cotton-candy stuffiness that crept in through her nostrils and clouded her head.

She let go of the staircase rail, swayed, found her feet, and strolled over to the dining room, hoping for pretty built-in cabinetry. Pretty built-in cabinetry could distract her from a ringing in her ears and the uncanny sense that she had heard a voice say things like “angry” and “unloved,” because that was ridiculous. In all the years she’d been talking to houses, the houses had never talked back.

Except her own house, maybe—the one she’d lost to Andy being a vindictive dick, taking it away just because he knew she loved it. When that house had spoken, it’d said warm things, hopeful things that made her feel like all her decisions had been good ones, and that she was home—right where she was meant to be.

But that meant that houses must be wrong sometimes, because look how that had turned out.

Even though she’d done all the work herself, on her own time, at her own expense… and even though she’d saved up the whole down payment and gotten the mortgage herself, rather than going back to school for two more years and having something to show for those student loans…

It didn’t matter. According to the state, Andy had as much right to the house as she did.

Or that’s what his lawyer told her. Everybody already knows that lawyers lie—it’s part of the job. So maybe it wasn’t true, but she couldn’t afford to fight it. It was either take half the sale price, or let Andy have the whole house, and walk away.

Dahlia pushed her own house out of her mind. She had work to do. She concentrated on the clean-stamped footprints she’d left in the dust—little trails from the front door, through the foyer, to the staircase, then back across the sitting room to the dining room where, yes, there were pretty built-in cabinets. A whole wall of them, thank God.

She went to the nearest one and leaned her forehead and palm against it, touching it like she’d reached first base, and now she was safe.

“Safe from what?” she muttered. “Jesus, what the hell is wrong with me?”

Deep breath. There you go: pretty built-in cabinets. Push the fog away; it’s only dust from plaster and pollen. It’s only an antihistamine away from being solved. Concentrate. Ignore it, and you can beat it. Talk through it.

“We can save these. Some of them.” She didn’t speculate how many, or what they would cost. “That chandelier—oh, God, look at it. Original, I bet. Somebody wired it, somewhere along the way—but whoever he was, he did a nice job. I’ll be super careful when I take that out. And this table…” Solid and heavy. Quartersawn oak—with too many layers of varnish, but that was easy enough to fix. It was old, but not as old as the house. “Maybe I’ll keep this for myself. I’ll find some chairs to go with it, and put it in my new place. My home is not as nice as this, but better than letting anybody throw it away.”

She went on speaking to the house, instead of to herself.

She found her bearings again, and the strain behind her forehead retreated to a dull nuisance. A good sneeze might banish it altogether, but her nose only rustled up a dull leak. She wiped it away with her sleeve.

Onward, to the kitchen. She found it on the other side of a door—a Dutch door, which was kind of odd for an interior feature, but you couldn’t let anything in an old house surprise you. “People love Dutch doors,” she said, checking the fastener and seeing that yes, it worked just fine. It would open in one piece, or just the top half alone. “We get asked for them all the time. People want them for back doors, and porches… they want to keep pets and kids inside.”

The more she spoke, the calmer she sounded, and the calmer she felt. Back on solid ground, even though she was parting out the body before it was dead. It was awful, but it beat a migraine.

She kept talking, and the headache kept going away.

“The kitchen’s tiny, but I could’ve guessed that. It was all redone… maybe in the sixties? Seventies? Most of this is garbage, and I don’t expect you’ll mind if we toss it, now will you?”

She paused, half afraid she might get an answer, since she’d asked the house so directly.

When nothing replied, she continued. “Anyway, I’ll check the attic… or wherever some of the old appliances might be stashed, if anybody thought to keep them. I’d love to find an iron stove, or an icebox, or that sort of thing. Oh, I ought to check the carriage house,” she remembered suddenly. “Fingers crossed that the Withrows never threw anything away.”

Outside, she thought she heard the distant crunch of tires on turf. Time was running out. Soon, she’d switch into boss mode, business mode, what ever mode would get the job done. But for just a few more minutes, this wasn’t a job. It was a sanctuary.

This sanctuary had a porch, and a pantry, and a door that likely hid a back staircase. Dahlia skipped those for now. She wanted to see the second floor, while she still had a moment of privacy.

Back to the grand entry with its swooping staircase. Each step Dahlia took added new prints in the dust. Up on the land.ing, there was a hall with a carpet runner that was a sad and total wreck; moths had gotten to it, so its pattern was lost to the fluffy gray mush the little winged devils left behind.

Now, how many bedrooms were up this way? She began to count, but was interrupted by a noise from outside.

Yes, definitely tires. Definitely trucks, coming past the metal bar slung between two poles, which served as a gate. Tick went the clock, and a flare of anger spiked between her eyes—but that wasn’t fair. This wasn’t her house. This was her job, and their job, too. But God, she wanted them to stay away just a little longer. No. A lot longer.

She hurried through her resentment.

First door, water closet. Added or renovated sometime in the late fifties, if she judged the Mamie pink and the fixtures correctly. Ugly as hell, but some people really liked that stuff. At least the sink was savable, and so was the tub. If they were careful with the tiles, and if there was time, they could keep those, too. Some hipster someplace would be fucking delighted.

Second door, bedroom. Bed inside—a big four-poster, no mattress. No other furniture, save a rolled-up rug that was almost certainly as tragic and bug-ruined as the runner in the hall. Third door, jammed shut—but she could open it later. Fourth door led to another room, not as large as the others so far; but something about it—some faint odor, or lingering sensibility—suggested a lady’s boudoir. Maybe a dressing room, since the house was so big and (if Dahlia understood correctly) the Withrow family was not. If Augusta Withrow was the last, then either their fatality rate was appalling, or there were never very many of them to start with.

A truck door slammed outside. She shrugged it off and kept going.

Yet another bedroom. This last one was the master, unless there was an even bigger, or more nicely appointed one, someplace else. It didn’t seem likely, given how grand this space was—and it had a bay window similar to the one in the parlor, but considerably bigger. The fireplace was one of the two with marble on it, and there were original fixtures left around the room. Antiques, too—regardless of what Augusta had told Dahlia’s dad. The stuff in here wasn’t junk, it wasn’t cheap, and it included a king-sized bed, along with a matching wardrobe that looked like walnut. She also saw two lamps with reverse-painted glass shades, and a cedar hope chest that just might have saved its contents from the moths.

Only two additions took the edge off the nineteenth-century charm: At some point, someone had installed a ceiling fan, and a rusted-out window AC unit jutted precariously into the room. Knowing good and well what a Tennessee summer felt like, she was prepared to forgive the retrofit.

“Dibs,” she declared of the room in general, though there was no one but the house to hear her. The bed didn’t have a mattress, but the bay window’s double-wide seat was bigger than a twin-sized mattress. It’d suit her sleeping bag just fine.

On the far side of the bed was a door. It wouldn’t be a closet, she didn’t think, and upon inspection, she was correct. It was a bathroom, added around the same time as the pink horror in the hallway—circa World War II. When she turned the sink’s handle, the faucet sputtered and coughed, eventually producing brownish-red water that went clear in a few seconds. She wouldn’t want to drink anything from those pipes, but they’d be fine for bathing, hosing things down, or running the wet saw, if they needed it.

“Definitely dibs, so I can have my own bathroom. And good on ol’ Augusta, for keeping the water and power on. Or for turning it back on, what ever.”

Of course they’d have to shut down the power toward the end, and use the generator in the back of her truck for all the equipment. When the real heavy work began, they’d be cutting into walls. Any live electrical system would be a hazard.

Another truck door slammed, harder and louder than was strictly necessary.

Now she heard voices, easily recognized. A window must be open somewhere, for her to catch them so clearly. It sounded like they were just outside the bedroom door.

She poked her head out into the corridor again.

Ah, there it was, down at the end: a window that wasn’t open, but broken. It was a six-pane grid with two panes missing. No wonder the sound carried so easy.

Dahlia left her officially dibbed quarters and peered through the glass, down at the salvage trucks. They were parked so near to the house she might’ve dropped a penny on the nearest wind.shield. Beside the trucks, her cousin, his son, and Brad-who-was-no-relation were chattering about the house’s exterior. The porch spindles were cool. Some of the gingerbread cutouts weren’t rotted out completely. Nice front door.

She turned away. Her time was almost up, and it wouldn’t do to waste it.

At the other end of the hall she found a second staircase, this one narrow and dark. She felt around on the wall for a switch, but didn’t find one, so she climbed up anyway. She felt a string dangle across her cheek and shoulder. She tugged it, and an overhead bulb crackled to life, revealing dark paneling on one side, and floral paper on the other. A recessed spot on the wall suggested a gas lamp fixture. The fixture was missing, leaving only a shadow and a warm-looking stain.

Out on the front lawn, someone called for her attention. “Dolly? You in there?”

It was Bobby, who damn well knew better than to call her that. She declined to respond. Really, she couldn’t possibly hear him, inside that stairwell that was scarcely wide enough for her to walk without rubbing her shoulders on the walls. That was her story, and she was sticking to it.

Her boots were heavy, and so was their echo on the steps, and under them. She paused, kicked gently, and yes—it was hollow under there. Storage? She hoped so. People leave great things behind in storage, when they’re done living someplace.

At the top, a trapdoor stopped her.

She pushed her palm against it and it moved easily, letting her up inside a spacious semi-finished attic. It was mostly empty, with no promising crates, trunks, or boxes; but she saw stray books, and the suggestion of toys. Old toys could be worth a mint. She’d take a closer look later on.

She stood on the stairs, her head and shoulders in the naked space—all of it lit by the attic windows (not leaded, not valuable) and as dusty as everything else. It was warmer by a few degrees up there, which made the air feel stuffy. In the exposed rafters overhead, she saw elaborate spiderweb clusters, nets, and balls; and she detected the nibble marks of rats or squirrels (please let it be squirrels) and, along the floor, drop.pings from the same (prob ably rats).

“Rats aren’t so bad,” she told herself, and mostly meant it. “The rats will give you gifts, and the bugs will give you kisses. Right, Dad?” Could be worse. Could be rabid raccoons, or needle-toothed possums. Besides, any rats in the Withrow house wouldn’t be the big black plague rats of lore, but little brown wood rats from the mountain. Give ’em fluffy tails, and you’d feed ’em peanuts in the park.

“Dahlia?”

This time it was Gabe calling her name. She dropped the trapdoor back into place and headed down the stairs—then over to the broken window, which opened when she yanked on the latch. She hung her head out, and hollered: “Up here, boys. Come on in, and take a look around.”

“We can’t.” Brad shielded his eyes against the sunny morning glare. “You locked us out.”

“I did no such thing… ?”

“Then the door locked behind you. Come on down here and let us in,” Bobby pleaded.

“Well, shit. Hang on.”

Dahlia left the window to stand at the top of the grand staircase and gaze across the first floor. The door was, in fact, closed. Had she shut it? No, she was pretty sure she’d left it ajar… but then again, old places, old floors, old frames, old hinges. She hadn’t heard it move, but that didn’t mean that the wind, the warped wood, or some quirk of gravity hadn’t seen fit to shut it anyway.

She took the stairs slower than she could have, stalling the inevitable every step of the way. She didn’t want to let them in. She didn’t want to start work on the Withrow house. This wasn’t some favor she was doing for an old friend; this wasn’t a restoration gig to preserve a landmark. This was a vivisection, a slow slaughter of a thing on its last legs. She loved the house, and she loved all its parts, so she hated her job, this time. She didn’t want to take anything. She wanted to fix everything, but that wasn’t up to her.

The door was indeed locked. Its dead bolt was turned.

Maybe she’d shut the door without thinking. All right, maybe—but Dahlia was about 90 percent sure she hadn’t done the dead bolt. Ten percent was a hefty margin of error, though, and she’d been lost in her own head, hadn’t she?

Lost.

The house was insistent, but its defensive resources were few.

On second thought, Dahlia knew good and well that she must’ve locked up without thinking about it after all. It was exactly the kind of thing she’d do. She was still dragging her feet. Still barricading forts that had already fallen. Scavenging mementos. Harvesting organs.

But it was like she’d told the house in the first place: It wasn’t her decision to make; it was just her job to sift through what was left. Did that make it easier, thinking of herself as more archaeologist, less grave robber? It still sucked.

She unlocked the door. “Come on in, guys.”

Excerpted from The Family Plot © Cherie Priest, 2016